R.B.4

1

A /

V

W O M A N &

A V I E W

2 0 0

7 / 8

|

|

1

SERIAL NO.

IM

448199

|

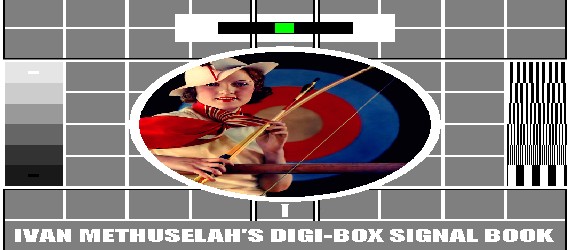

IVAN METHUSELAH'S

DIGI-BOX SIGNAL BOOK

6: HIGH

DEFINITION

The first successful

television transmission was at 30 lines. In 1936, the BBC launched the

first High Definition service at 405 lines (that's a pixel height of

377 in today's money; the rest of the lines are nothing to do with the

picture). In the late '40s, France experimented with an 819 line (755

pixel) system before joining with the rest of Europe at the new PAL

standard of 625 lines (576 pixels) that we've all been living with

since BBC 2.

Now there's a bigger fish in

town, and its name is HD. HD is 1080 pixels high. Fantastic!

Of course life is never

simple. In 1964, when BBC 2 launched, we all had to go out and buy

ourselves new tellies so that we could see the 199 extra lines of

resolution. Those new tellies were dual standard receivers and could

switch between the two line-systems. My cathode ray could flip from one

standard to the other with little difficulty. It helped that everything

was smaller in those days. But as the resolution gets ever larger,

certain problems begin to raise their heads. Before we address these,

we need to understand the lay of the land.

INTERLACE

|

In the beginning was the

Cathode Ray. It buzzed around the place like a cat on fire. Cathode ray

tubes (CRT) scan the picture in two passes -- odd lines then even lines

-- to create a frame. They do this at 50Hz, which is faster than the

eye can see. It takes a 50th of a second to create one field of

alternate lines, and another 50th to fill the gaps, but we just

register that as a 1/25th frame. Everything was lovely unless you had

super-fast eyes, in which case you'd collapse in a heap, dribbling. But

most people don't have super-fast eyes. The world is lovely. But the

bigger the picture gets, the further the cathode ray has to travel, and

oh... it's not as young as it used to be. 1080i (1080 pixel interlaced)

CRT tellies exist, but they're like platinum dust. And of the few that

exist, even fewer can manage to squeeze an industry standard 1440

horizontal pixels onto the screen. Not with their backs like they are.

Which is unfortunate, because HD is currently broadcast in 1080i. The

best way to see a 1080i picture is on a 50Hz CRT television of

appropriate resolution (where it would look something

like this). But who buys CRT these days? You can buy sheds

that are smaller.

No, no no. Now we have LCD

and

plasma: lovely flat tellies that take up next to no room at all. You

can even hang them on the wall without need of a flying buttress. Now

the trouble is that such tellies don't do interlace well. Their pixels

are either on or off, so there's no dying luminescence to aid memory,

and what we end up with is a flickery mess with a load of bouncing

lines in it (these demonstration images have been treated to reduce

this problem, but even then the simulation can only go so far). To

counter this, LCD and plasma do something called: |

|

Simulated interlace

(720x576)

|

DEINTERLACING

Now really this should be a

piece of metaphorical piss: take one field of data (the odd lines),

take the next field (the evens) and superimpose. Ta da: one

deinterlaced picture ready for show. This technique is called "weaving"

and theoretically it is that

easy. But here's the rub:

interlacing isn't limited to display, it's also the mechanism by which

most TV cameras traditionally operate. And because a camera scans its

fields in real time, the result is that one field shows material

recorded 1/50th of a second before its partner. Now the human eye

couldn't care less so long as it gets to see this stuff interlacing:

the brain can't move quick enough to process the difference properly

and so shrugs and says "it's something like this". But glue the two

frames together and it's a different matter, because suddenly they're

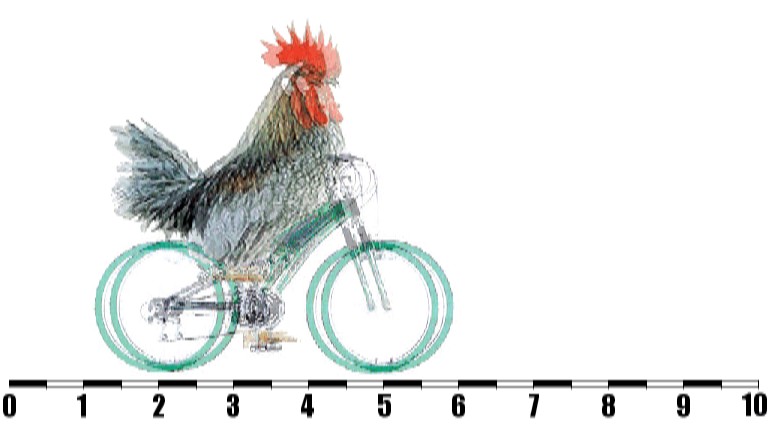

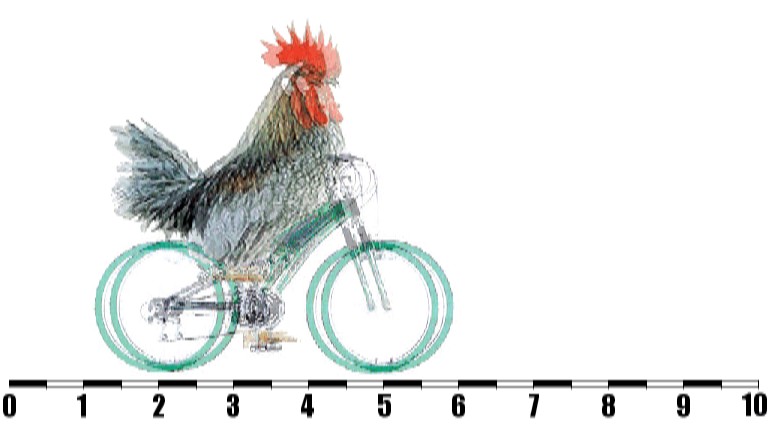

up long enough for our brains to make them out. Now imagine I am

recording a chicken riding a bicycle at a speed of 1 foot per second:

that chicken will have moved a quarter of an inch between one field

scan and the next, so gluing the two images together will result in a

very odd looking chicken:

Appropriately

enough, this problem is called "combing". How do we get around it? We

can get rid of the lines by blending the frames like so:

But

that still hasn't got rid of the ghosting problem. In fact all it's

done is effectively halved the vertical resolution. Perhaps we need to

take a different approach.

This

time we'll take each field

of alternate lines and double them up: so we have line 1, then another

line 1 in the gap where line 2 goes later, then line 3, then another

line 3, etc. We do this for each field and then play them all back at

50 frames per second. The result appears bottom left (cropped to save

room).

When objects are in motion, the results are pretty good, but notice the

meter at the bottom of the frame: bits of it are dropping through the

pixel grating

to create a flashing effect. Things are even worse for our testcard

(bottom right).

Bob Deinterlacing

Bob Deinterlacing

(50 Hz)

|

|

|

This

effect is rather charmingly

called "bob". We can, of course, get rid of it by dropping one of our

newly created frames and going back to 25 frames per second. This would

give us the same temporal resolution as film, and that's more than

enough. But we'd've achieved this by halving the vertical resolution.

Bob Deinterlacing

(25 Hz)

|

|

|

Half the vertical

resolution of HD is 540 which is less than the vertical resolution of

conventional telly. Half the vertical resolution of conventional telly

is 288 which is considerably less than we used to have in the pre-BBC2

days. A 544 horizontal resolution picture would come out looking like

the one on the right if anti-aliasing were applied.

Half the vertical

resolution of HD is 540 which is less than the vertical resolution of

conventional telly. Half the vertical resolution of conventional telly

is 288 which is considerably less than we used to have in the pre-BBC2

days. A 544 horizontal resolution picture would come out looking like

the one on the right if anti-aliasing were applied.

What we have then are a number of mechanisms for deinterlacing, none of

which are truly ideal. Plasma and LCD televisions have a little

computer inside them to combine these techniques and apply them as

computer thinks best. Different methods can even be applied to

different parts of the picture, employing similar motion compensation

methods to those used in the GOP manipulations. The results are

variable. The picture on a plasma or LCD display is at the mercy of the

deinterlacing gubbins inside. The same is true of 100Hz televisions,

which repeat frames or interpolate median frames in an attempt to

reduce flicker.

Of course, not all material being broadcast is filmed using interlacing

cameras. Anything on film and anything using swanky new

progressive-scan digital cameras should deinterlace without a problem.

If you spend all your time watching DVDs, your progressive-scan

television should really be perfectly up to the job.

The vast majority of stuff broadcast at the moment is not HD, and not

recorded on film. It is safe to assume that the best TV cameras are

being used for the HD output and consequently most of the non-HD

material is likely to be using interlacing cameras. As far as

conventional broadcasting, this state of affairs is only a problem to

LCD and plasma viewers. But there is another complication on the

horizon...

HD is 1080 pixels tall. Normal telly is 576 pixels tall. That's not a

particularly neat fraction. To illustrate the problem in a gratuitous

manner, this link shows you a standard

definition interlaced picture (a little buzzy when seen on a computer

monitor, but you get the idea), and this link

shows you what happens when you try to blow it up to HD proportions (if

you have a browser capable of resizing web-content, why not play around

with that function and see if you can't induce seizures). Ok, like I

say, that's gratuitous: we've got to deinterlace the thing anyway. But

that should serve as an illustration as to why deinterlacing is

especially important in upscaling a conventional broadcast for a HD

television. Watch what happens when we blow up the deinterlaced images

we created earlier to HD screen-size:

50 Hz Bob Deinterlace of a 720x576 picture;

Anti-aliased 25 Hz Bob

Deinterlace of a 720x576 picture (i.e. ignoring every other field)

and the same at 544x576;

A straight blow-up of a 720x576 picture,

which could be achieved using the weave-deinterlace method we looked at

originally (ideal for still images).

Here then we begin to see a problem with HD televisions. Let's compare

a strong signal on a standard definition CRT with the same image

weave-deinterlaced for progressive scan and then blown up for a high

definition TV (bare

in mind that the interlaced CRT image is shown here at a reduced

palette to enable animation, and that its brightness has been

compromised to

reduce flicker on progressive-scan displays):

|

|

Resolution: 720x576 (detail)

|

These images represent the best

possible output of a 720x576 broadcast testcard in SD and HD display

formats.

Now let's do the same thing to ITV2 (I'll not bother with another

interlace animation because the reduced palette of the animated .gif

isn't really up to the job):

Resolution: 544x576 (detail)

That's starting to look quite crumby,

especially the enlargement, but

we can make it even crumbier: we can deinterlace it badly and lose half

of

the vertical pixels. Then it looks like this:

...and once blown up to HD size it looks

really rather grotty indeed, as demonstrated, right. All these

enlargements in this section are being done by your browser. Imagine

how smeary they could look with some really bad anti-aliasing thrown in

for good measure.

It is this question of upscaling, confounded by deinterlacing, which is

the biggest problem for HD. It's like if I were to upscale the AVWoman

address-bar icon by the same proportion:

|

|

|

|

Film, and digital

material shot in progressive-scan, are less

troublesome because their genuine 25 frames per second (or 24 frames

buggered about with, in the case of film) can be deinterlaced easily

with no fear of combing or the like. And, of course, a programme

recorded on filmstock can be telecined (or otherwise digitized) and

broadcast in full HD resolution.

This link depicts a mock-up of what a

top-end HD cathode-ray TV knocks out given a UK standard 1440x1080

resolution HD broadcast. This link shows

what it looks like on progressive-scan systems when deinterlaced to the

highest possible standard, and this link

shows what it looks like when deinterlaced by an idiot. Even the idiot

failed to destroy things irreconcilably. In fact, let us compare the

low quality deinterlace with the best quality SD image (blown up to

equivalent size):

Standard Definition:

720x576 enlarged to 1920x1080 (detail)

|

|

High Definition:

1440x1080 deinterlaced to 1440x540 (detail)

|

This represents the best SD can

hope to be, alongside the worst HD can be, given an equivalent image

compression. Now step as far away from your monitor as you would

normally be from your TV. There you go. In this case at least,

sub-standard HD broadcasting looks better than top-standard SD

broadcasting.

So what do we draw from all of this nonesense? Clearly HD looks

yummy-scrummy, but the trouble at the moment is that you can count all

the currently available HD channels on the fingers of one badly mangled

hand, and you can count the number of programmes of interest on those

channels on the same gory wreckage. Until digital switchover hits your

local transmitter, you won't be getting terrestrial HD, which means

you'll need to harness a satellite. Freesat's performance is similar to

that of Freeview (bandwidth

allocation tends to be a little higher, so picture quality should

generally be slightly better) but with more channels (though some

curious omissions too). In the longer term it is a safe bet that,

apocalypses allowing, HD will be coming to a television near you within

five to ten years. And to watch it you'll need a compatible lot of kit:

as UK HD broadcasts are 1080 pixels tall, don't go buying a 720 or 768

tall display. If you're able to find a CRT telly, make sure it has at

least 1440 pixels of horizontal resolution in order to match the

current broadcasting standard. And consider the fact that a TV display

in the video world is the equivalent of an amplifier and speakers in

the audio world: if the telly doesn't have a tuner capable of spotting

a HD signal, you will need to buy a separate.

The most important detail emerging from this study is, I think, the

question of deinterlacing and upscaling. Standard definition

broadcasting far far outnumbers HD output at present so if you are going to buy a HD capable

television then please please please buy a decent one: one that can

take a 576 pixel tall interlaced signal and not render it as a Turner

seascape.

My advice to you is this: if you have a standard definition cathode ray

telly and it is working fine, for Baird's sake don't trade it in for a

HDTV just yet, because it'll only make you want to Oedipus your eyes in

a desperate and misguided attempt to improve the picture. If it's on

the blink and all that is available is plasma or liquid crystal, then

buy a HD one but buy a good HD one. And remember, kids, even if your

main telly is not HD ready, your computer monitor almost certainly is.

Why not slap a HD tuner into your USB port and try it that way?

Above all else, remember that watching telly tends to be done at a

distance anyway, and that even the crumbiest picture looks OK after

three pints (though decidedly worse after seven). What's more, a

lenticular magnifier fastened to the screen can turn a black and white

picture into the most extraordinary technicolour.

Now scroll back up and look at the chickens again. You know you want to.

Half the vertical

resolution of HD is 540 which is less than the vertical resolution of

conventional telly. Half the vertical resolution of conventional telly

is 288 which is considerably less than we used to have in the pre-BBC2

days. A 544 horizontal resolution picture would come out looking like

the one on the right if anti-aliasing were applied.

Half the vertical

resolution of HD is 540 which is less than the vertical resolution of

conventional telly. Half the vertical resolution of conventional telly

is 288 which is considerably less than we used to have in the pre-BBC2

days. A 544 horizontal resolution picture would come out looking like

the one on the right if anti-aliasing were applied.